Interview with Sol León and Paul Lightfoot

text: annette embrechts

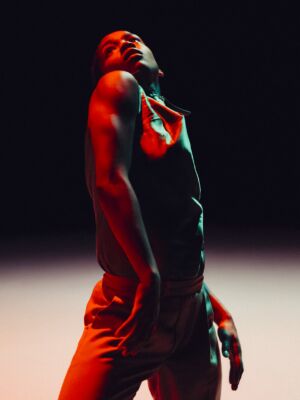

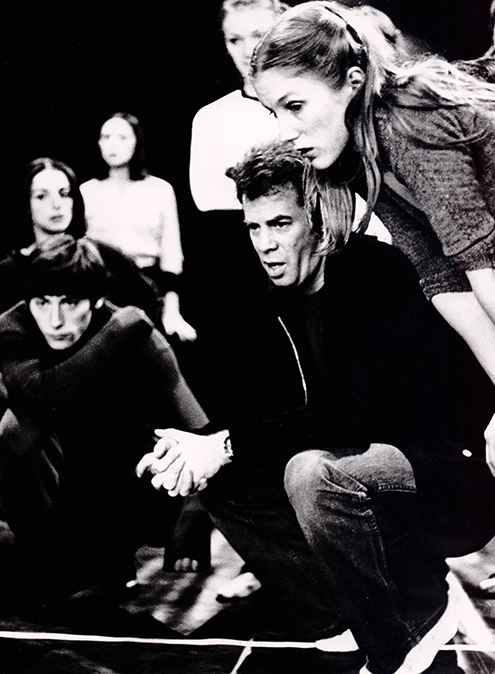

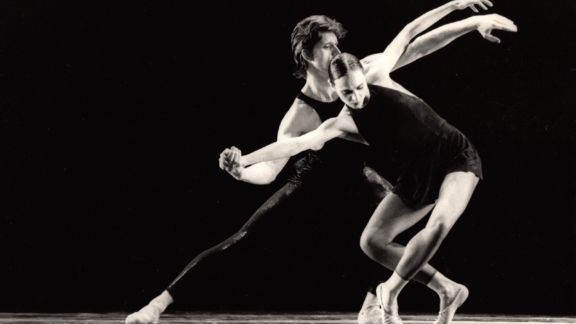

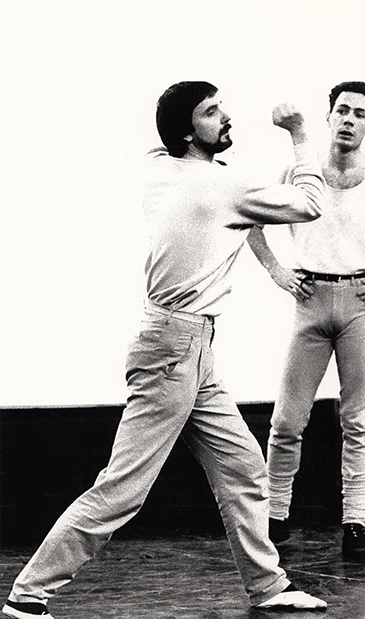

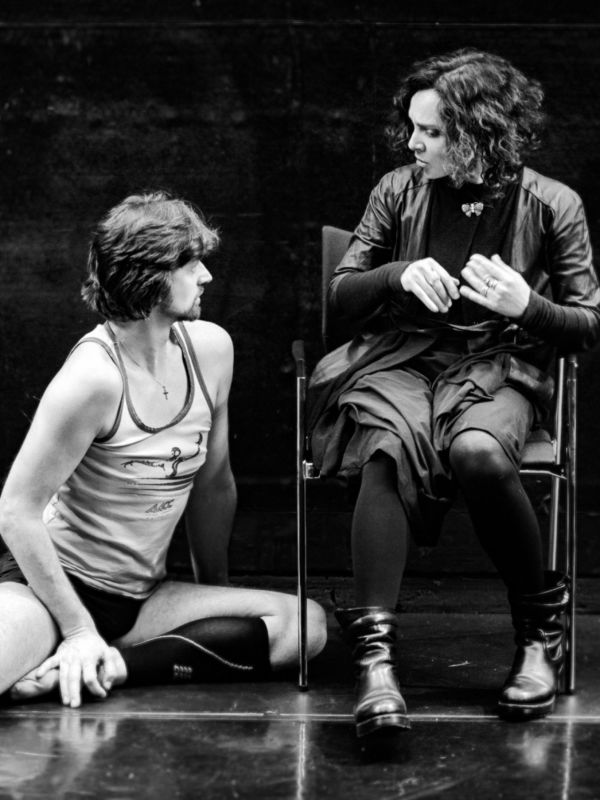

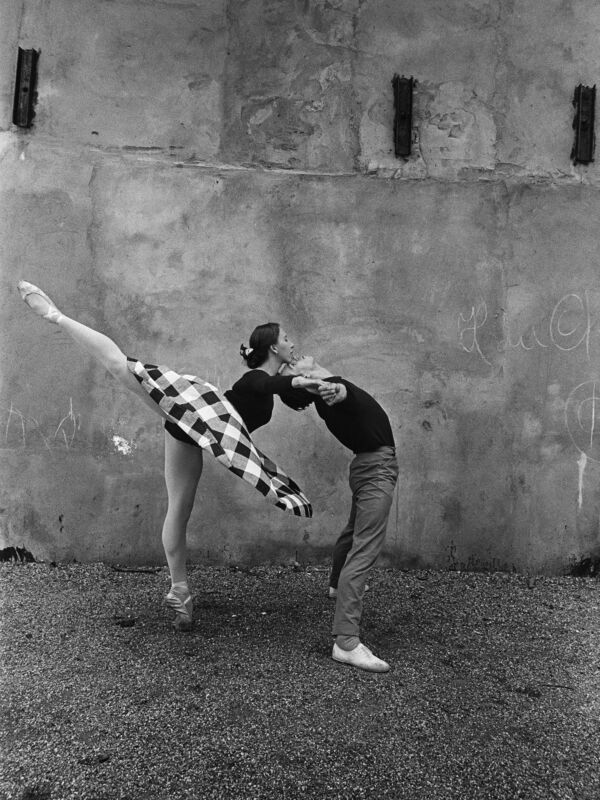

Halfway through the 1980s, both of them arrived at Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT), both of them coming from different traditions of dance. Paul Lightfoot (Kingsley, England, 1966) was educated in classical ballet at a famous institution namely the Royal Ballet. In The Hague, he found the creativity and freedom he was craving for. From a young age, Sol León (Cordobá, Spain, 1969) performed Spanish folklore dances for tourists and compensated for what she lacked technically with her sense of expression and creativity.

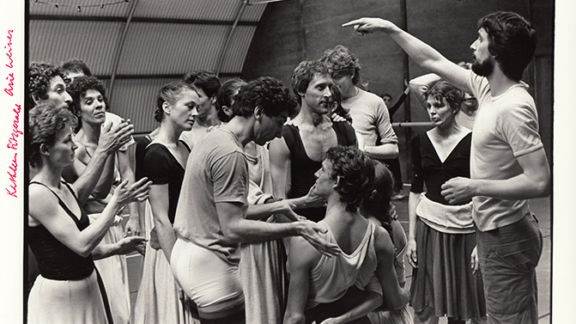

Joining NDT, they both immediately felt that “this is our home.” 30 years later, they are part of the artistic top of the company in The Hague and look to the past and the future of its sixtieth anniversary. They agree on one thing: although NDT is a large company, it remains a small community. “A loyal core of around ten creative daredevils always stokes its beating heart with its boundless energy.” Looking back, they are astonished. Have they really been part of Nederlands Dans Theater for over thirty years, half of its sixty-year anniversary that will be celebrated with a jubilee program in October? Leon elaborates, “The lifetime of a dance artist goes by at a rapid pace at an energetic company such as this one.”